Chapter XXIV

Benefits Remembered

The last of the senior examinations vanished cloudlessly under the sky of blossoming May and left not a wrack behind. “Not even a flunk-note,” sighed Myra in relief when her mail continued agreeably innocent of unstamped envelopes.

The fortnight’s vacation preceding Commencement opened with an afternoon spent on the beautiful river. It was a quiet ride — that last one all together, with the rocky shores slipping past them, the water lapping against the sides of the boat. Myra flitted to and fro like a witch, leaving ripples of laughter in hen wake. Ruth roamed from bow to stem, leaning over the rail to stare at the waves that raced below, or climbing to the upper deck to watch the hills. At times they skirted so near the cliffs that she spied the red columbine flaunting its bells. She knew where at home in the mountains the lovelier purple columbine fluttered its butterfly wings beside the brooks. That was one comfort: there would always be flowers even when the class had scattered from the Atlantic to the Pacific. Then Ruth drifted across to the corner where Lydia was holding court under the awning, and sat rather dose to her for a few minutes, her hands lying idle in her lap.

Elinor moved watchfully here and there, chatting to a doleful one or smiling with the merry. Why couldn’t the girls all be more thoughtful about saving the occasion from dismal failure, she wondered. There was that peculiar person who had written the Founder’s Day poem — a splendid poem, too — but why in the world did she persist in turning her back and propping her cheeks on her fist in that misanthropic fashion? The poet when gently asked if she were not feeling well, replied in gruff tones that she was getting an impression of the scenery. And Elinor refrained from noting any possible mistiness of her lashes.

Of course there was singing of songs specially composed for the day. In the dusk of their return to the college they sang all the way up the avenue, though in a somewhat spasmodic manner. After half-an-hour’s rest and sundry renovating touches of toilets, away they trooped to the gym for the annual Senior Howl. Here during the progress of the supper at long tables strewn with maidenhair ferns, the sophomores serenaded them from beneath the windows. It sounded very sweet, but Myra for one was glad when the voices ceased, for at the last verse Elinor had looked as if on the verge of tears. That would have been perfectly horrible under all those bright lights with everybody watching her.

The senior vacation slid past with incredible rapidity. One beautiful day after another — forenoon and afternoon and night. A few of the students rented a sewing-machine and made their own Class Day gowns. Lydia carried Ruth to the city with her for an interview with their family dressmaker concerning a certain white organdie for Commencement, as Miss Allee was to read an essay at that dread time. Myra’s express parcel from home contained a transparent white frock to be worn over a white slip on Commencement and over rose-color on Class Day. Elinor was to be daintier than ever in the fine real lace which her mother brought.

“Elinor isn’t one bit like her mother, is she?” confided Myra to Ruth during an interval in her duties at the candy booth on the Saturday of the senior auction. Desks and chairs and lamps and rugs, which were to be left behind by the graduates, had been put on sale in the lecture room that morning.

Ruth had wound her way through the crush of purchasers and “genuine bargains” to notify Elinor that the elocution teacher was waiting for her in the Chapel. Myra’s remark caught her in a moment of wistfulness after the mother and daughter had turned away in response to the message — one shyly eager in her lissom girlishness, the other with a remote though pleasant air and something of severity in her longer, straighter lines of feature and drapery.

Ruth followed them with her eyes. “Yes,” she said slowly, “they are different: one is womanly and the other is scholarly.”

“Oh, but, Ruth, oh, dear me! What’s the use of college if you can’t be womanly as well as scholarly?”

“You can be both at once more or less, but —”

“But not equally?”

“I’m afraid not. In a harmony there is always one color that catches the eye, one strain that holds the ear. It is the same with a harmonious character.”

The word sent Myra’s wits cantering forward. “That reminds me: I am to wear pink, you know. Oh, won’t it be terrible if the girl who happens to match my height and so walks with me should be someone in yellow?”

Alas, poor Myra! Although she escaped this particular calamity another more frightful still fell upon her when Class Day arrived. Not until an hour after the ceremonies, when the guests and the girls were strolling in softly tinted groups over the green lawn in the fragrant twilight, did someone exclaim over the omission in her toilet. She had forgotten to put on the rose-colored under-bodice to match the underskirt. There she had been marching so proudly over the winding canvas path in the brilliant sunshine with cameras snapping to right and to left of her in a dress that was tinged only half-way with pink!

It was a comfort to reflect that the catastrophe would have been far worse if any of the other three had disgraced herself so agonizingly. Tall Ruth would have displayed longer stretches of the contrasting halves. Lydia was conspicuous as marshal, walking alone stately and slow between the class and the six sophomores who bore the massive white-and-gold cable of the daisy-chain. For Elinor the affliction would have been worst of all because she as president sat almost in the center of the platform upon which the seniors were arrayed before the fluttering sea of fans and faces in the out-door amphitheatre.

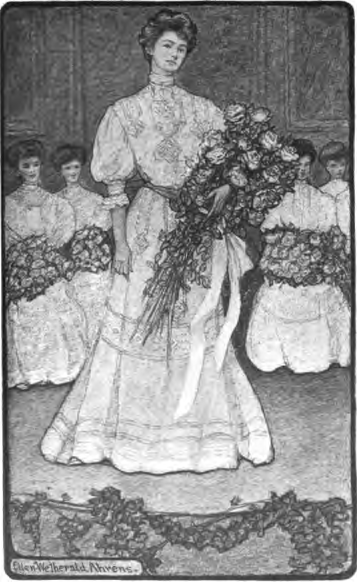

Elinor in misty white, with the class flowers swaying over one arm, rose to welcome the audience, and then again to introduce each speaker on the program. Mrs. Offitt sat in the front row of spectators. Ruth’s eyes seeking to trace some resemblance in the thought-worn features rested there one long wonderful moment. There was no one in the world to gaze at her like that.

In the evening Japanese lanterns swung in festoons along the avenue, and the Glee Club sang out in the June darkness. Within doors an orchestra played while the kaleidoscope throng assembled and reassembled, shifting and circling through the parlors, scattering up and down the corridors to gather here and there in the pretty senior studies. There were mothers and aunts and sisters; there were fathers and uncles and brothers and cousins. Some of the honored parents were too proud and happy to talk; others were too proud and happy to keep still. Everywhere were seniors on hospitable duties bent and too busy to waste a grieving thought upon goodbyes. Numerous sophomores loitered on the stairs and pondered sadly over how much they would miss all these seniors the next year. Then after ambuscading the maids who were carrying trays of striped ice cream they conscientiously ate all they could and wandered away to their own rooms with speculative stares at certain closed doors behind which various classes were holding reunions. They felt very sorry for poor old alumnae.

The next day brought Commencement with its pomp of black-robed trustees and faculty upon the platform and white-gowned girls in the pews. Ruth looked unique — almost distinguished — in her willowy height. Afterward the girls told her how much they had enjoyed her essay. Some even said that they wished it had been longer — which was a veritable compliment on such an unexuberant occasion.

The audience was invited to remain for a collation in the dining-room later. Myra declared that a “collation” tasted to her considerably like salad, ice cream, olives and so forth. She refused to resign her precious diploma even while she cut the cold tongue into bits. She explained quite frankly and truthfully that her sheepskin represented a greater amount of manual labor than the others because she had written out several examinations more than once.

In the afternoon there was a packing of trunks and a flying hither and thither on last errands. In the evening came the Class Supper.

From the sweet June dusk outside belated sophomores wandering arm in arm sent inquisitive glances through an unshuttered window into the brightly lighted lower room where a table had been spread along three sides of a rectangle. They saw the seniors eating, though not very hungrily. Now and then one rose to respond to a toast and sat down amid clapping and laughter. Four girls in turn read from slips of paper — doubtless the class prophecy, for the attention of the listeners appeared to be concentrated upon one conscious face after another till each had acknowledged her fate with an embarrassed smile. After that the secretary called the roll, and every name was answered by yes or no — almost invariably no, it must be confessed, for the question was, Are you engaged? At several of the replies the unconscionable sophomores could actually hear the incredulous hooting.

By this time the feasting was over, and the revelers, quickly grave after the jesting merriment, leaned back in their chairs. Here and there one absently fingered the fern frond that lay nearest on the white cloth. Presently the assemblage seemed to have resolved itself into a regular class meeting, for Miss Offitt, even yet with an effect of shyness in the lines of her half-unconscious bending toward her listeners, called them to order and spoke earnestly for a few minutes. Then Miss Howard rose and discoursed at such length that the sophomores outside grew impatient of seeing her stately shoulders still marking the same height against the wall every time they passed the window.

When at last she resumed her seat, a brief discussion ended in a scene somewhat peculiar. Now here, now there, along the table, one girl after another stood up and uttered a sentence or so before sitting down hastily as if deprecating notice. Miss Howard glanced at each speaker and wrote a line on a paper in her hand. In the course of ten minutes or more of spontaneous volunteers, the pauses became longer and the faces more reflective. Two or three of those who had already taken part appeared to add a word to their previous statements. At every speech the others clapped their hands.

After the meeting had been adjourned, the doors swung open and the new alumnae scattered magically in fear of long good-byes. Through the corridors desolate with trunks and packing-boxes Myra fled in pursuit of her three friends.

“A dreadful person commenced to wish me a happy life instead of a pleasant summer! I ran —” she fell into step between Ruth and Elinor with Lydia close in front. “Isn’t it a splendidest plan to found a scholarship as our class gift to the college! I wish that I had promised another hundred from my uncle. He’ll do anything I say, particularly if he is obliged to. My fifty is only part of my graduation present, and I’m afraid I won’t miss it — that is, not enough really to do me good.”

“Didn’t the girls take it up in the loveliest way!” Elinor’s eyes were aglow. “When we talked it over in the afternoon with mother, she was doubtful whether we could succeed. It will be hard work to raise the full ten thousand before our fifth anniversary.”

“Fancy! Imagine! Elinor Offitt, the rebellious granddaughter, sponsor for keeping an extra poor miserable captive chained to her books for four years at a time! I’m surprised! I’m amazed! I’m — I’m jiggered!” and she hugged with both arms impartially till Ruth gasped for breath and Elinor writhed free, her face rather unwarrantably flushed.

“It was generous of those girls to pledge the first money they will earn after they are out of debt,” she hurried the words, “it makes me feel worthless.”

“I am glad that there was no hysteria,” said Lydia, “and yet they were enthusiastic enough. I believe that nobody was tempted to give emotional promises. She fluttered the paper slip between her fingers. “The fund will start at near two thousand dollars.”

“Wh-what?” exclaimed Myra in astonishment.

while Ruth cried, ” Two thousand! But I thought I kept track of the sums, and they amounted to just about half of that.”

Lydia bit her lip, but in the half-light of the alleyway no one observed this unusual demonstration. “One of the girls,” she hastened to explain, “preferred to make an anonymous donation in addition to her nominal gift. I should not have mentioned it just yet. By the way,” she continued quickly, “enough of us for a sort of reunion are planning to come up to the first Hall Play in the fall. We shall get up some kind of a report about the fund at that time. The Washington members intend to earn a few hundred with an entertainment this summer and the southern —”

“I’m coming,” interrupted Myra, “even if I have to walk. Ruth will be here because she isn’t going west till later. Elinor’s the only one of our crowd who won’t be present. Ho, Elinor! Dear kind sweet noble Elinor, why not surrender that year in Paris? Oh, yes, and Athens, of course. Renounce such vanities. Let your brother go abroad alone and bear all those long-anticipated troubles by himself. Why not stay at home a while and then come back with us in the autumn to this little monotonous hole?”

“Perhaps I will,” said Elinor.

“My sakes!” ejaculated Miss Dickinson, looking around for a place to sit down suddenly, “Good land!”

Lydia’s hand dropped from the gas-jet “Why, Elinor!” she protested in an oddly startled way, “oh, but, Elinor, that can’t be the reason. Surely you could spare it —?”

Under the flare of light the gray eyes were lowered swiftly to hide a peculiar glint in their depths. But Ruth must have spied it, for she was smiling to herself. And Myra, catching a glimpse, was on her feet in a twinkling.

“Oh, I see, I see! You’re the anonymous girl! It’s your Paris money, and now you can’t go. You’ve given it up for the sake of sending another girl to college. You — you — you — ” her voice choked and she flung her arms around Elinor’s neck, “you blessed idiot!”