CHAPTER V.

WITHOUT A “CHARACTER.”

When I informed Annie that I had been discharged, she exhibited the greatest concern, for to her mind my condition was a pathetic one. How should I get another place without the character Mrs. Allison would refuse to give ? She argued that it was always better to part friends, even with bad mistresses, for without a character no girl could get a situation.

I made a note of this for future reference, and since I left service I have found it a useful bit of information. If many much-tried but good-natured mistresses would only remind impertinent and neglectful maids that future situations depend upon present good behaviour, a great stride would be made toward a solution of the servant problem. On the other hand, the time will come when references will be demanded from the mistress as well as the maid. Then the Mrs. Allison type will not be so numerous.

Poor Annie! She was holding one hand to her head and another at her side, while she discussed this question, displaying her unselfish interest in my welfare. She had lost four hours of legitimate sleep the preceding night, but was up at six in the morning as usual. What wonder that she felt tired and ill! I counselled her to go to bed and rest awhile. She looked at me again with the superior air she had worn on the evening of our first meeting. “When you’re in service, you can’t go to bed if you’re ill,” was her answer, as she carried the tray of silver and glasses into the pantry, and commenced her first day’s work as bond-fide parlourmaid. She had only a servant-girl’s headache, brought on by remaining awake till after one o’clock in order to open the door for the daughters of the house, who had been to the theatre! “But how avoid such occasional contingencies ? Shall the young ladies be allowed a latchkey?” asks a horrified mother of grown-up daughters. Well, of course, to my unconventional mind, the latch-key would be the simplest way out of the difficulty; but I would suggest that it is the duty of the ladies’ maid and not of the parlourmaid to wait up and serve supper after the theatre. The parlourmaid must rise early in the morning to begin her daily round of work, and therefore should be allowed to go to bed at a proper hour, while in the case of the ladies’ maid it is, or should be, different. If she is up late, she should be allowed to sleep later in the morning. Of course, in large establishments of a dozen or more servants these matters are better arranged; but in households like Mrs. Allison’s, where the strictest economy is practised as regards the number of servants employed and the amount of wages paid, little or no attention is given to this important subject.

Mathilde, the Swiss maid, was a person who well appreciated her own value and took advantage of her position. She was a competent dressmaker and hairdresser, who, for reasons known only to herself, elected to give her services to the Allison family for the small stipend of ^20 a year. Realising that cheapness and competency rarely go together, Mrs. Allison knew that she would be unable to fill Mathilde’s place at such a price, and decided it was best to humour that young woman’s whims. Mathilde was of a sleepy nature, and could not be induced under any consideration to sit up after 10.30, so either Annie or I must remain down-stairs till all the family were in. It was Mathilde’s duty to help me make the best beds, and while thus engaged I noticed that she had a patronising way of treating me. She was particularly inquisitive in regard to my previous life and occupation, and I told her a highly-entertaining story concerning myself.

The new cook was a welcome acquisition in the kitchen. Annie was especially glad to have some of the responsibilities taken off her shoulders, and the domestic machinery began to run a little more smoothly. My labours, however, were in no way lightened, except that I had nothing more to do with dish-washing.

Annie’s duties were to rise at six o’clock, attend to the lamps, sweep and dust the large music room, carry some boiling water to Mrs. Allison, lay the table, wait at all the meals, clear away and brush up afterwards, answer the door, and assist with the needlework. Her duties seemed neither so numerous nor so complex as my own, but when I explain that from half-past nine in the morning until eleven at night the bell rang on an average of every ten minutes it will be seen that her time was well occupied.

Mary, the cook, was tall, fat, ruddy-faced and good-humoured, and seemed inclined to make me her especial protege. She expressed regret when I told her I was to leave the next Thursday, and gave me the address of a lady in Belgravia who she thought could offer me an easy place. At dinner she was greatly exercised over the news that neither beer nor beer-money was allowed in the kitchen, and blamed herself for her stupidity in forgetting to ask about so important a matter before she took the place. Beer, she declared, was essential to her health and happiness. Then she beamed upon me, and, handing me a pitcher, asked if I would run around the corner and get some bitter ale, as she could not leave the joint that was roasting before the fire. I did not wish to offend her, nor did I quite like the idea of going to a public-house; but finally, as I stood there halting between two opinions, journalistic enterprise got the better of dignity. I threw on my hat and coat, and, with the despised pitcher in hand, made my exit from the area gate, determined to penetrate into the mysteries of the bar-room.

As I entered there came an odour of tobacco that nearly overwhelmed me, but I went forward to have my pitcher filled. There was over a score of men and women standing or sitting about on the long benches, drinking, smoking, and gossiping about what “she said,” what “he said,” and what “I said, sez I.” Some of the men were in livery, and I was the only one of my sex without a cap and apron. A number of those present I recognised as servants in neighbouring families. They seemed in no hurry to return with their beer, and, judging by their hilarious state, many of them had been there some time, and various family secrets were divulged by one servant to another. I left the place with my pitcher of ale, which I tried to hide by means of a large morning paper and the cape of my coat. I had seen the result of allowing beer-money to servants, and I appreciated more keenly why so many of the letters I had received in answer to my advertisement had ended with the words “No beer.” I found that the public-house was made a sort of rendezvous for the men and women servants of the neighbourhood, and housework lagged behind, while with pipe and beer they gossiped and dragged out family skeletons for the edification of their fellow-servants.

This question of beer-money is a much more serious one than many housewives imagine. I am speaking now from a purely business standpoint, for I am not a distributor of temperance tracts nor a member of a prohibition union. I can see no reason why beer or beer-money should be demanded by servants as one of their lawful rights. If, when their day’s work is done, a glass of ale will help to take away “that tired feeling” with which they must necessarily be afflicted, I would not be the one to deprive them of their comforter; but I do insist that the mistress of the house should not be called upon to furnish the beverage, nor should they under any circumstances be allowed to go to the public house to procure it. A business man in the city is not expected to furnish a daily allowance of beer to each one of his clerks; and, if domestic service is to be raised to a proper standard, this matter of beer-allowance must be dispensed with.

Mary was what is commonly called a plain cook —not a “professed” one, as she confidentially informed me; and when I noticed her way of preparing potatoes I decided that she was a very plain cook indeed. Her only ideas seemed to be either to boil them and send them up whole, or sift them through a colander, from which they emerged in dirty, rice-like flakes. She added no milk, butter, pepper, or salt, and I began to feel sorry for the family who were obliged to eat the —to say nothing of my own personal longing for some of the sixteen delicious dishes into which I knew potatoes could be made. Mary began at once to save up all the drippings from the roasts, and did not heed my remark that dripping was good for frying. She demanded to know whether I wanted to rob her of her lawful perquisites. When the bone-man came around, I believe she was richer to the extent of sixpence, while Mrs. Allison was poorer by a much larger amount.

I soon discovered that the cook had a prejudice against washing frying-pans, which, each time bacon or fish was cooked, were hung up in the scullery with the cold grease sticking to them, all in readiness for the next time they were needed; and it was only a matter of chance if the fish-pan was not used the next day for frying eggs. Another discovery I made was the reason why so many pieces of beautiful china soon get unsightly with the enamel all marked by an intricate network of dark cracks. It is done by putting the dishes into the oven or on the stove to heat before being taken up to the dining-room. This can be avoided by immersing the plates, meatplatters, and vegetable-dishes in very hot water and drying quickly just as they are ready to be sent upstairs. The heat of the oven not only cracks them, but imparts a peculiar odour not likely to increase one’s appetite at dinner.

After the cook came, the three beds in the servants’ room were occupied, and, to my immense relief, Annie and Mary shared one washbowl, and left me in solitary enjoyment of the other. When we went to bed sleep did not come so easily as it had at first, for an exchange of opinions on various subjects was the order of the first hour or longer. Mary was curious to know all about the personal characteristics of each member of the family; but Annie was uncommunicative, and told her, if she stopped long enough, she would find out for herself. I was treated as a sort of heroine, Mary praising me for my pluck in asking for better breakfasts, which she declared her own intention of doing soon, and Annie always bewailing my characterless state. Mrs. Allison had advertised for a new housemaid, and Annie regaled us with an interesting description of all the girls who applied for the situation. At last a housemaid was engaged to come in the next Saturday.

“Why does she not come Thursday, so Mrs. Allison will have someone to take my place at once ? I asked.

“Oh, a girl don’t like to go to a place as soon as she’s engaged. A nice servant never does it,” answered the cook.

“And why not, if it will accommodate the mistress?” I demanded.

“Well,” said Mary, “I can’t tell ye. I don’t know as there’s any pertickler reason, only they don’t like it. Why, the missus wanted me to come a week ago, saying she was so put to without a cook; but I wouldn’t do it. I don’t approve of hurrying things like that.”

By the dim candlelight I could see a self-satisfied smile on Mary’s face, and I questioned her no more, concluding that servants, as well as other people, had a right to do things “on general principles” without assigning, or even having, any reason for their actions.

“I don’t think I’ll stay here after this year,” remarked Annie, as she began to unbutton her boots.

“Why not?” I asked. “Don’t you like it?”

“Of course I don’t. Nobody could like such a hard place. But that isn’t the reason. I’ve been here over a year now, and two years is long enough to stop in any place, good or bad. You get used to doing things the way to suit one missus, and, if you stay too long, it’s hard to learn to suit other missuses, so I believe in changing round —that’s my opinion.”

Saying which, she threw her boots in the middle of the floor, and put her head under the pillow, instead of upon it. She always slept that way, and I suspected that it was done to soften the clanging of the alarm-bell which rang out fiercely at six every morning. I did not always follow Annie in her line of reasoning, and I could not quite understand her objections to stopping a long time even in a good place; but I put it down to the fact that she, like the cook, acted sometimes “on general principles.”

Annie, on the whole, was a good servant. She took pride and interest in her work, and had at first impressed me as being very conscientious. My faith in this latter quality was a little shaken by an incident that happened one day in the drawing-room. It was before the cook came, and she was helping me to wash some of the more expensive pieces of bric-abrac. I sat on the floor with a pail of water and a cloth, cleaning some ivory and marble figures. I put a small statue of Mercury into the pail, took it out, and beheld that it was headless. I was bewildered, for I had been particularly careful in the process, and I knew I could not have knocked it against the pail. As I sat with the head in one hand and the body in the other, Annie startled me with, “The missus is coming! Hide it quick, or she’ll see it! “

“Of course, I shan’t hide it,” I retorted, angrily; and then Mrs. Allison came towards me.

“Oh, I forgot to tell you, Lizzie, that several of these figures have been broken and glued together, and ought not to be put in hot water. Lay it aside] and I will mend it again.”

Annie looked crestfallen and ashamed. Mrs. Allison spoke pleasantly to me in those days. That was before I had offended her by asking for better breakfasts. Afterwards she sent me to “Coventry,” and -never looked at me except with forbidding brow.

Up to Wednesday I had escaped the scrubbing, for, when I turned out the young ladies’ rooms the day before, I carefully arranged that twilight should come on before I got to that part of the work. Then the occupants were obliged to dress for dinner, and I would be in the way. Besides, the floor must not be damp when they went to bed, so they smilingly informed me that I need “never mind” about it. From that time I was their true friend, and when Miss Allison lay on the bed the next day with a jumping toothache I took my bottle of Pond’s Extract to her and insisted that frequent applications would help her. In the evening, when she and Miss Blanche went to the theatre, I whistled for a hansom and helped them in with all the good grace imaginable, stepping up in front and closing the doors very carefully, so as not to catch their dresses. I even ceased to use “language” in my heart when pretty Miss Blanche, who had operatic aspirations, went from room to room screaming “a-a-ah” up and down through all the different keys. Both of them always wished me a cheery ” Good-morning,” even after I was discharged, and I have only the most pleasant recollections of them.

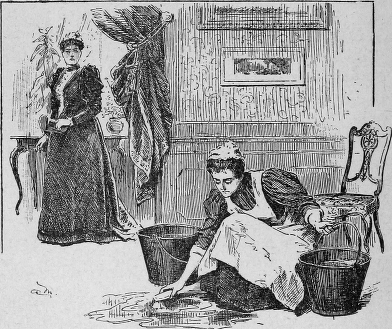

When, on Wednesday afternoon, the decree went forth that I should take up all the rugs in the drawing-room and scrub the floor, I felt that the evil day could no longer be put off, though how I was to carry through my commission was more than I knew. I dared not confide my ignorance to anyone, for when I engaged with Mrs. Allison, I assured her that I had never been a servant, but had learned how to work at home, which was true enough—at least, I thought it was, for I knew the chapter headed “Housemaids,” in the book on “Servants’ Duties,” by heart. But that chapter had said nothing about scrubbing. I suppose the literary lady who wrote it lived in a house where there was no scrubbing to be done. Thus I was utterly in the dark as to how to go at my task, and was obliged to follow my own ideas on the subject. I took from my cupboard two pails, one half full of soapy water, the other containing fresh water for rinsing, and with flannel and brush I started out to do or die, or both. From the conversation with the charwoman, I had gathered that it was proper to go on one’s knees for the operation; but she had said that a former servant in this family had got housemaid’s knee by kneeling on the cold floors. It was not part of my plan to contract the disease, and then I was afraid of soiling and wetting my print dress, which I wished to keep fresh and neat-looking for my next place.

In scrubbing that drawing-room I kept two ideas in mind : first, to ward off housemaid’s knee; second, to keep myself and costume out of the wet. So pinning up my frock, I took the brush and assumed a squatting position, hopping about from place to place. I scrubbed a square yard at a time, then rinsed in clean water and dried it, congratulating myself the while that I was something of a Columbus in my way. I had nearly finished, when, glancing toward the folding doors, I saw Mrs. Allison looking at me, her large black eyes burning with anger. Had I been on the ground-floor, I am sure I should have jumped from the window and precipitately departed from my situation, so dangerous did the lady of the house appear.

“Well, a pretty servant you make, I must say! Any girl with half a grain of sense would know how to scrub. You haven’t even got general intelligence!” was the announcement that burst from her. Now I had always been told that I had a large bump of combativeness and was able to hold my own in a dispute; but this time I was speechless, feeling that my position really was untenable. I had nothing to say in my own defence; but a sense of the ridiculous overcame my prudence, and I smiled blandly in Mrs.Allison’s face. She uttered a contemptuous, impatient “Oh! “and left me.

I hurriedly finished the room, put the rugs and furniture in place, and, perched on the top of the step-ladder, polished the looking-glasses with tissue-paper. The steps were more than twice my own height, and when I attempted to lift them from one part of the room to another I found it a case of “when Greek meets Greek,” and was obliged to pull them along after me as best I could.

That evening Annie again broached the needlework subject, fearing, I suppose, that I would go on the morrow and leave her to clear out the mending-basket I had postponed it as long as I well could, without admitting point-blank that I was unable to cope with the task, so I determined to do unto Annie as I would have her do to me under similar circumstances. I remembered to have seen my mother put a wooden ball into the toes and heels when she darned stockings, and I asked Annie for the darning-ball. She had never heard of such a thing.

“But I must have one, or I can’t darn them,” I insisted.

She brought me an oval-shaped soda-water bottle.

“Maybe that’ll do. It’s sort of round,” she said.

I thought it would, and, feeling that “well begun is half done,” I attacked the enemy, and darned to the best of my ability. If the wearers of those stockings got bad feet on account of the lumps and seams, I can only say I am very sorry, and pledge my word to avoid mending-baskets hereafter.

On Thursday I washed out all the dusters and made my cupboard as tidy as possible preparatory to taking my departure. Mrs. Allison did not speak to me again after the scrubbing episode. When at six o’clock I informed her that I was ready to go, she silently handed me six shillings, which was really liberal, for she only owed me five shillings and fourpence halfpenny. I thanked her and said good-bye, but she did not answer. I do not doubt that long before this she has realised the bad taste she displayed in thus showing her temper.

In my story of my life at Mrs. Allison’s house I have spoken of her only as a mistress. Some of my friends who know her personally have assured me that, socially and intellectually, she is a most charming woman to meet. I did not go into her house as an enemy or detective to pry into her private affairs. Although many opportunities were given me for doing this, I refused to take advantage of them. I was a journalist seeking information on a certain subject. She happened to answer my advertisement, and was the first person who offered me a place, which I accepted. I have given an account of my experiences at her house as a servant; that is all. Mr. Allison, who is a man well known in the professional world, was always pleasant with me; Mr. John Allison, the eldest son, treated me politely, but always with dignity; while the nice ways of Master Tom won my admiration from the first. Miss Kate, the youngest member of the family, went to the country shortly after I arrived, and I saw little of her.

When I left Mrs. Allison’s house I went to a jeweller’s and left the six shillings she paid me to be made into a bracelet. Then I jumped into a cab and was driven to Mrs. Brownlow’s in Kensington, where I was to enter another situation; this time as parlourmaid.