The Old New Sexy

The thin ideal is often discussed as a topic for feminism,4 and it is, but that’s rather like saying that bread riots are a problem for public order. First, lets get the skinny on skinny.

The age at which girls experience menarche (first menstruation) was not very different in the distant past, compared to today.1 One notable exception was the industrial revolution.

…and chronic illness and accumulated childhood hardships (e.g. poverty, poor nutrition, exposure to alcoholism or tobacco smoke, physical neglect, death of a parent) delay menarche as a stress response… It is likely that the high levels of disease and poor nutrition associated with rapid social and economic change in the nineteenth century pushed the mean age to artificially high levels2

The average age was estimated to be seventeen1 in some places, which suggests that there were cases of even later onset. One study reports that a quarter of the skeletons examined belonged to people living in medieval London who had not completed puberty before they died at age 22-25.2

These are people who were literally starved and tormented into sterility.

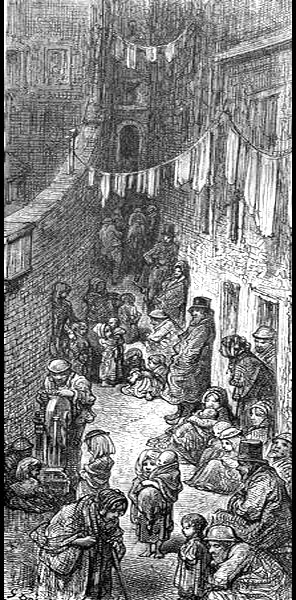

Prostitution in Victorian London’s slums was big business, and attracted not only local clients, but middle-class sex-tourists. Most of the women who took up the trade did so before the age of twelve. And why not? Sexual abuse in the slum was unavoidable; there was only the question of compensation. It seems unsurprising that the chronic poverty and stress, combined with over-crowded living situations, should cultivate abuse. And here’s the magic: it also cultivates sterility. A girl can have a decade-long career as a prostitute while still being technically a girl. At a time before reliable contraception, girlhood was a commodity.

Consider that the same level of poverty is keeping a 19th century man from being able to afford a family, so an infertile girl is going to be what he actually can afford. Whether she is a prostitute or simply another poor wretch, she is going to be skinny.

This is unprecedented in human history. Before the 19th century, plump, or ‘rubenesque’ women, were considered the ideal.3 After all, they are most likely to carry out successful pregnancies and survive illness. It makes most sense for a man to pick a winner, not a loser. So when the loser body type became the ideal, the waif arguably became the poster child for a very dark version of capitalism.

This strange tale grew even stranger when skinniness became an ideal of the late 19th century middle class. Women, who could most afford to demonstrate their reproductive fitness, sought the opposite. Corsets and dieting became all the rage. Anorexia appears for the first time. We can only speculate why. Did it have to do with the fact that unmarried men were having their sexual interest re-calibrated by girls with whom they were having sex? Whatever the reason, the capitalism look was in.

One observation that might be illuminating here is that the female body ideal became more buxom in the 1950s: big breasts, narrow waist, and big hips. And the reason might have had something to do with men’s ability to afford families again: The massive industrial capacity required by the war had been converted to civilian consumerism. Veterans found well-paid factory jobs and educational opportunities. It was the golden era of the stay-at-home mom. It was an economic era in which wealth was more evenly distributed than any time thereafter.5

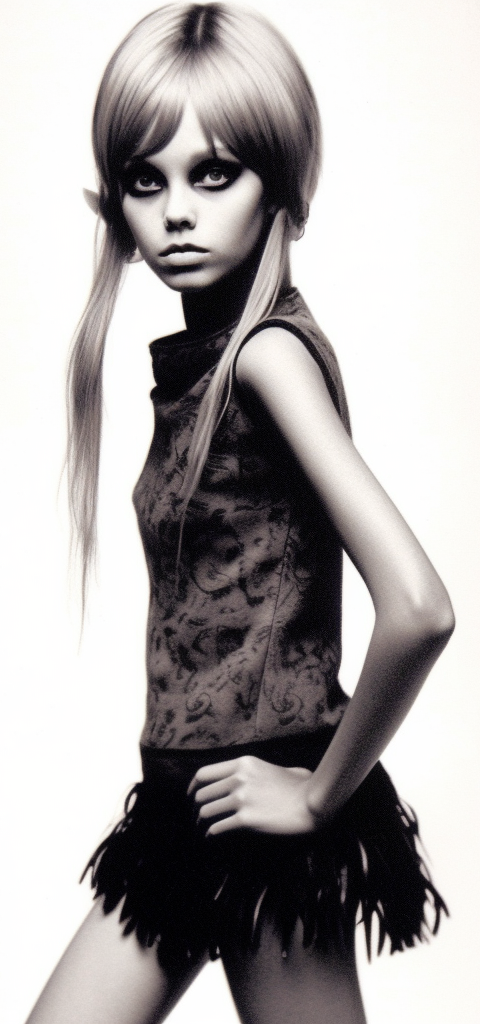

By the mid-1960s, the thin ideal began creeping back into fashion, perhaps not coincidentally with a creeping increase in wealth disparity. Women ultimately were forced by economic necessity to return to the commercial workforce in the 1970s.6

After twenty years of more growth in wealth disparity, even the removal of pubic hair became fashionable. In an age in which people have less economic power than their parents,7 infertility is the new sexy. Or rather, the same old new sexy.

1. Papadimitriou, A. (2016). The Evolution of the Age at Menarche from Prehistorical to Modern Times. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, 29(6), 527–530. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2015.12.002

2. Am J Hum Biol. Jan-Feb 2016;28(1):48-56. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.22761. Epub 2015 Aug 4. On the threshold of adulthood: A new approach for the use of maturation indicators to assess puberty in adolescents from medieval England. Mary Lewis, Fiona Shapland, Rebecca Watt.

3. https://theconversation.com/womens-idealised-bodies-have-changed-dramatically-over-time-but-are-standards-becoming-more-unattainable-64936

4. Thin is the Feminist Issue, Nicky Diamond Feminist Review No. 19 (Spring, 1985), pp. 45-64

Published By: Sage Publications, Inc.

5. Apel, Holger, Income inequality in the U.S. from 1950 to 2010 – the neglect of the political real-world economics review, issue no. 72

6. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1986/09/women-in-the-work-force/304924

7. https://edition.cnn.com/2020/01/11/politics/millennials-income-stalled-upward-mobility-us/index.html