The Awful world

We live in an awful world, and its purpose is to be awful. I recently read a story about a kind of eel that can escape the fish that had eaten it by backing out through the fish’s gills. That means the eels are eaten alive and would otherwise die a slow and painful acidic death in the fish’s stomach. There are insects that lay their eggs on paralysed hosts, which then eat the hosts alive upon hatching. This world is full of such horrors. These horrors exist because they are consistent with the physics of this world and branches of biology that could develop here.

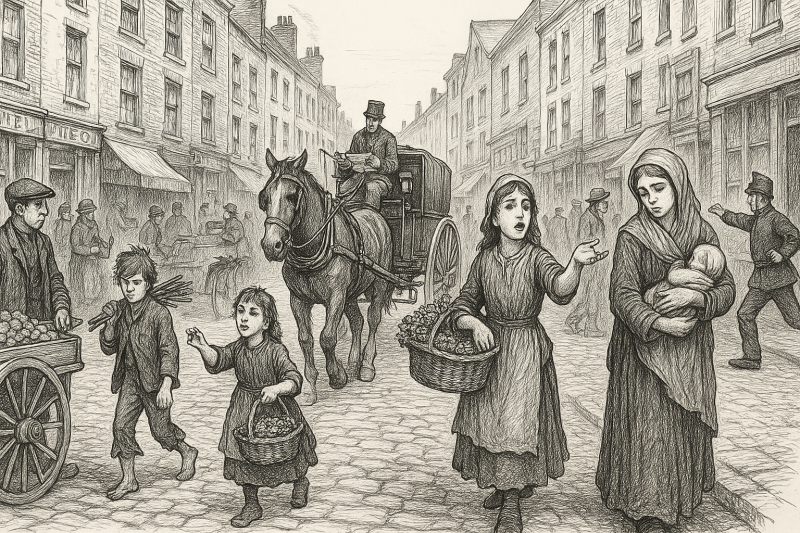

Human history is little more than a catalogue of second-order horrors. The treatment of slaves, the execution of pogroms, religious wars, domestic abuse, Dickens’ London, the treatment of prisoners by medieval lords — the list is very long indeed. There are only one feature of note: the horror is not consistent. There is no such thing as a hell which burns forever. Life must have the opportunity to regenerate itself in order to make possible new horrors. However, an inconstant hell is not less hellish. Any professional interrogator would confirm that constant torture is not as effective as inconstant torture.

There is another aspect worth considering, but it is rather an event and not a feature: ordinary people have had, for a brief moment, the relative luxury to reflect on this. Through the storms and tides of horror, a tiny island of relative calm has appeared at the end of the second millennium, in which ordinary people have had enough education and leisure to wax philosophic about their world. Hitherto, the only people with that privilege owed that privilege to the horror.

Because the end of the second millennium has spanned several generations, it seemed that the world was on an ineluctable path of improvement. 2025, however, has revealed that the apparent evolution was only a tide, which is now waning. Humanity is returning to history as usual.

So how are we to rescue a world that was never designed to be rescued? Obviously, we are not, but it is precisely the hopelessness of the project that liberates us. If there is anything to work on, it is ourselves.

There are only two possibilities here: (1) this world is all of reality and therefore nothing has meaning, or (2) this world is part of a greater reality in which our struggles matter more. What are our struggles? They at least do not entail embracing (1). What is the greater reality? We cannot say with any certainty, but we at least must attend to what we can see, and the only other orderly reality we can see is the dreaming world. At second glance, it is much more orderly than the proponents of (1) would have us believe.

Said more succinctly: we cannot know our true situation, but what we can do about it is clear: discipline our awarenesses according to our experiences in dreams. The reason is the alternatives are certainly meaningless. Dreams are only potentially meaningless.