The Halls of Power

26 Sept 1847

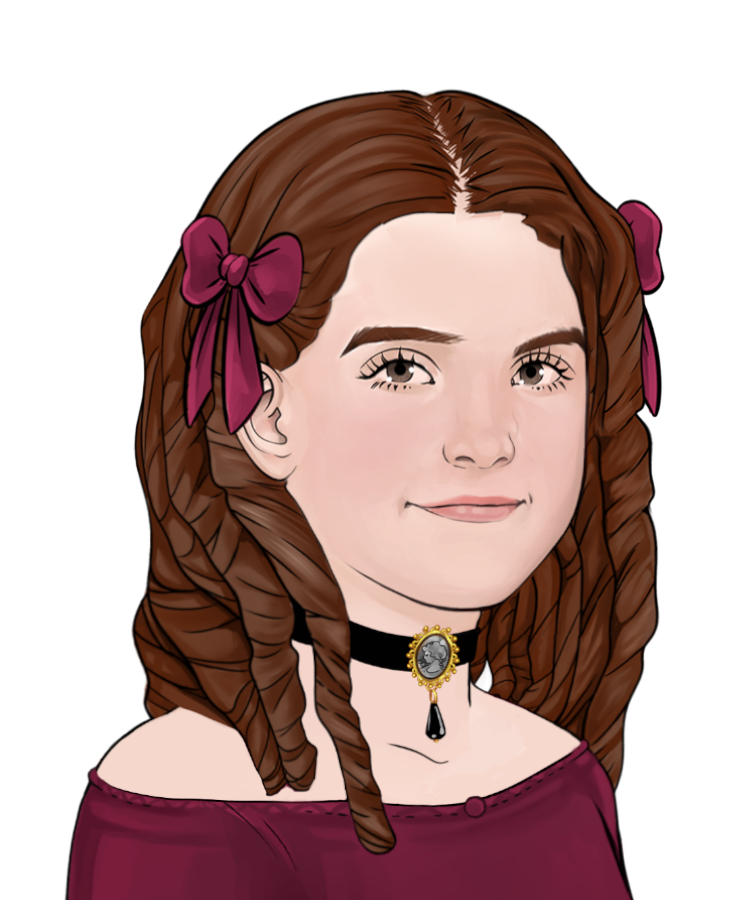

When I awoke the next morning, Cassie smiled weakly at me from the other side of the bed.

“How are you?” I asked.

“The worst is passed.”

“Cassie, Mrs. Landwell told me that if your illness were not kept secret, it would be subject to gossip. Why do you think she would say that to me?”

“Because, my dear pet, the halls of power are for trumpets, not for whispers.”

I felt belittled. Somehow, she was accusing me of not understanding the obvious. I lay on my back and looked at the ceiling. “What loyalty have we to power?” I asked. “We, who are willfully held foreign to it?”

“We are born in a world organized by centers of power,” she began. “All that is worth having is subsumed by one or another. We earn money to buy food and clothing. The land on which we live is not our own until we register with the bureau of deeds. The only alternative is to create a power center of our own — but this would not be tolerated by those who already hold power. We must subscribe.”

“And even if we must align ourselves with power, why may the truth not be trumpeted? Is the truth not a power?”

“Power is not attracted by the truth,” said she. “Else would our leaders be chosen from the faculties of universities; scientists would be the wealthiest of men. No, there are other criteria for the accumulation of power. And there are truths which can dismantle.”

Something inside me resonated with what she said, yet I found in myself no eagerness to surrender to it. I realised that her ‘female curse’ was the curse of being too close to someone of power. Like moths to a flame, females are warmed by proximity to power, but burned by contact.

“Did you call me, ‘My pet’?” I asked.

“What?”

“You said, ‘My dear pet, the halls of power are for trumpets’. Do you secretly think of me as your pet? Or was that merely a turn of phrase? Or may I not ask that?”

She laughed, “You may certainly not ask that!”

I tentatively ran a finger along the shoulder pleats of her gown. “Some people wish to be understood,” I said. “They wish their sufferings known. They wish to be comforted, or at least to believe that someone might wish to comfort them.”

“Yes?”

“And some do not. Do you have an explanation for the latter?”

There was no reaction to my query, so I began to repose it. “Miss Benton, do you know why some—”

“I know only the first kind,” she said preemptively. After a moment, she added, “Of which some wince from misfortune. Or give themselves to inhabitation of utter misfortune.”

“It sounds dreadful.”

“No.”

“How so, no?”

“To angels, chamber pots are dreadful.” She turned to look at me with her big, soft, brown eyes. “To us, they are a convenience.”

How am I to understand this? There is no insight that would not break my heart. As this was not her intention, nor to her taste, I let it not be broken.

I realigned myself to lay my cheek on her chest. “I think I’m someone’s pet. I do. But I’ll not say whose.”