Elinor’s Junior Year

Chapter XIII

Room for Contemporaries

The corridors were lined with trunks and alive with girls flying in and out of their rooms. Here was one lifting a tray of crisp white ruffles. There another unfolding herself cautiously from a prolonged investigation of the deepest recesses rose with a pile of books tottering on one arm. A third unwrapped tissue paper from a flower-laden hat with such tender care that a fastidious freshman who was passing at the moment decided on the spot that she was an awfully nice girl because she knew how to treat pretty things.

Ruth strolled into sight, her hands full of radiant nasturtiums, and paused to sympathize with a sophomore who was mournfully scraping bits of glass and raspberry jam from a woolly tam-o’shanter. A great rattling of castors beyond the transverse proclaimed the triumphant return of a searching party; and Myra and Elinor straightway appeared trundling a couch-frame by a long cord.

“Everybody keeps asking if we are settled yet,” complained Myra, rubbing her palm where the string had reddened it, “till we are too tired even to smile.”

She began to sit down gingerly for a rest on the edge of the frame, which promptly tilted, depositing her on the floor and sending the opposite side threateningly into the air over her head. Elinor, springing nimbly to the rescue, pushed it back into stable position with a bang.

“See here, Myra Dickinson, this is my couch and cost me two dollars and a quarter. In future you will kindly teeter-totter on your own property.”

“You broke my steamer-chair,” grumbled Myra as she propped her weary self against the wall, “and yet I put a cheerful courage on.”

“Ho! Put a cheerful courage on, did you? Because I happened to be underneath when it went down, that’s why. It wouldn’t have ripped at all if you hadn’t tried to sit on my lap.”

“Dear, dear! You two are certainly worn out. Run up to the orchard for a change. Never so many apples left before, and girls gathering them in scrapbaskets! The garden is sweet-sweet-sweet.”

“That sounds like a bird,” said Elinor with a keen glance at the face that seemed to glow under its pallor. “You’re glad to get back this year too, aren’t you? It is a beautiful place, as places go. I wonder if you care for the mode of life here or just the work. Imagine it a house-party or a summer resort with the same people and community intercourse but no insistent work. Would you still love it?”

“‘Blessed is the man,'” quoted Ruth lightly, “‘who has found his work. Let him ask no other happiness.'”

“Ah, yes, but Carlyle doesn’t say, ‘Blessed is the woman.'” Elinor stooped with apparent carelessness to pick up the loop of cord. “Work isn’t enough for a woman, you know. By the way, has Miss Ewers come yet?”

“I haven’t seen her,” answered the happy voice, “she ought to arrive at any hour now.” Ruth held the spicy flowers before her shining eyes. She was carrying these blossoms to put as a welcome in the room of this friend. For their junior year the other girls had chosen a suite for three on the fourth floor, with Ruth in a single on the fifth at the head of a neighboring stairway. All through the lonely summer Ruth had looked forward joyously to the prospect of living in that single, for was not Miss Ewers’ room close by? She would see her every day.

“I’m quite fond of Miss Ewers myself,” remarked Myra graciously, “we’ll have her in for fudges every little while and help break up the monotony of being a faculty with no fun going on. Isn’t it lovely to be a junior! Everybody says it is the best year of all.”

Here the bumping rumble of trucks sounded from the elevator; and Lydia appeared with a cast of Venus under one arm, a pillow under the other, while she marshaled a procession of her household goods drawn by two meek-shouldered men. She halted for a word, though her anxious gaze continued to accompany the desk that lolled unsteadily upon a packingbox, at intervals bestowing sly kicks against the tea-table in front.

“Girls, isn’t it provoking! Miss Ewers is not coming back this year.”

There was a moment of silence. Then Elinor’s hands fell with a thud upon the trunk at her side, and Myra stammered, ” B-b-but how did you hear?”

“I don’t believe it,” said Ruth slowly as if to herself. I don’t believe it. It isn’t true. It isn’t true.” The flowers in her grasp sent forth a spicier fragrance from their bruised petals.

“It’s true enough. Mrs. Vernon has just received a telegram to say that Miss Ewers has accepted a sudden call to another college. Better position, higher pay, more chance of advance, and so on. She’s gone, that’s all. The seniors are disgusted. What is it, Elinor?” for slender fingers had grasped her wrist with aching pressure. She followed Elinor’s warning glance.

“Ruth, I didn’t think. Do you care so much as that? Oh, Ruth, she is only a woman like all the rest of us. We are here with you. We are your friends. We won’t let you miss her. Her successor is a famous teacher. The English course will be better than ever.”

Ruth swayed in her place and brushed her hands across her eyes, the flowers dropping unregarded. “It isn’t true,” she repeated dully, “I don’t believe it. It can’t be true. It can’t, it can’t, I tell you. I don’t believe it. Lydia is always making mistakes.”

Lydia’s brows lifted in indignant amazement. “Do you think that if it were only a rumor —”

“Hush!” Elinor laid a finger on her lips. “She’s dazed. It was a shock, didn’t you see? She doesn’t even hear us. We mustn’t let her go away by herself. There, she almost staggered. Come, Myra.”

They sped after the hurrying figure. Elinor reached her first end slipped a firm arm around her waist. Ruth pushed her violently away.

“Leave me alone!”

Myra sprang forward barely in time to save Elinor from falling, but Ruth passed swiftly on without a backward glance.

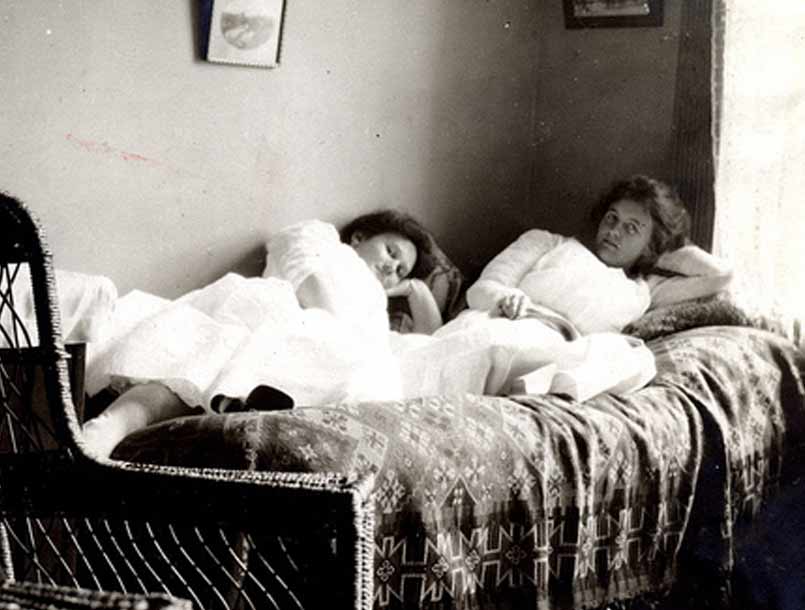

Then followed twilight days for Ruth when the girls were like vague forms gliding by at a mistily indifferent distance. She seemed to have forgotten how to smile. The voluble regret of other students irritated her, worn and nervous as she was after her exhausting summer newspaper work.

One afternoon Myra raced up the tower stairs and rattled the knob of Ruth’s locked door. The older girl rose from the bed, where she had been lying face downward, and turned the key. Then stepping quickly to the high window, she stood with her elbows on the sill, her face set steadfastly toward the purple hills beyond the hazy river. Taken aback at sight of the forbidding posture, Myra paused for an abashed moment. Then with a confidingness that had been nourished by her petted home life, she moved nearer and reached out to pat one limp hand.

“I know how you feel, Ruth, I know exactly how you feel.”

After a minute of maddening exasperation Ruth snatched it away. “You do it merely to be kind, and I wish you would leave me alone.”

Myra drew back with a hurt little gasp and stood watching the desperately averted profile. A sudden piteous quiver of the compressed lips won her to hurrying words. “Ruth, we do love you — all of us. We didn’t at first maybe so much,” she explained honestly, “because you seemed so different from everybody else. But now it wouldn’t be our crowd at all without you. Lydia says that you are one of the finest girls in college and she fully expects to be proud to claim acquaintance some day. Elinor declares that you have wonderful ability, though — though — oh, well, she admires you tremendously even if she doesn’t understand you. I’m awfully fond of you, Ruth. Why, the new freshmen have heard of you. I saw one point you out to another yesterday, and —”

“I used to believe that Miss Ewers cared for me,” cried the sore heart, “but she went away without a thought of how — how I’d feel. She has written only once, and she speaks about her energy being limited. That means that she does not wish to keep up a correspondence. She — she likes the other college better — and the other girls.”

Myra hesitated, her worried glance traveling from the white bedspread to the bare washstand, from the dusty desk to the curtainless window. An empty rose-bowl showed its dingy facets on the stone-ledge brushed by sprays of scarlet woodbine. Ruth’s favorite picture leaned its glass against the wall at her feet. She did not care how her room looked this year.

Myra inhaled a long preparatory breath. “You won’t mind, please, Ruth, if I — if I say something you may not like. Somebody told me this once, and I do believe it is true. A teacher who has seen hundreds of students come and go every year simply cannot care for all who admire her. She has got to hold herself indifferent. Oh, of course,” she added hastily at sign of an out-thrown protesting hand, “she likes some better than others — far better — but don’t you see it isn’t the same? She has her own friends — has had them for years and years and years. And so I think that you ought to try to care most for your contemporaries. Don’t you remember what Emerson says in Compensation about letting old angels ‘go that archangels may come in?’ You have always been so much absorbed in Miss Ewers that you neglected others. I’m quite sure that new friends will come to take her place. And anyhow even if she loved you better than her own contemporaries, still you could not ask her to give up such an opportunity as this?”

“Don’t I know that?” exclaimed Ruth impatiently, “but it — it hurts.” A silence; then: “I never have anything,” she burst out in passionate resentment, “you and Elinor and Lydia have everything — father and mother, brothers and sisters, homes and friends and money and all you want. But I — just when I find one friend dearer than the rest — who might take the place of all the rest — I — I — lose her. It is not fair. It is not just.” shut her teeth and stared drearily away across the river to the unchanging hills.

Myra swallowed hard twice. Was it always so discouraging to attempt to console people? After all, her sermon had not done one bit of good. Whenever she wanted to help persons, she made them feel worse than ever, and — and — Ruth talked dreadfully. Here she caught her breath hard and burying her face in Ruth’s skirt sobbed so heart-brokenly that the original mourner found herself thrust into the role of comforter.

“You little goose!” she pleaded with caressing pats and awkwardly soothing hugs, “now stop that, won’t you? You ought to stay away from this grumpy individual till she recovers from the blues by herself. I won’t mind after a while — perhaps. You see, I had planned for special work with Miss — Miss Ewers, and it takes time to adjust my ideas. It helps a lot to have you so sweet to me. Don’t worry any more about it, you little idiot!”

At this point swift steps fled lightly through the corridor below and mounted the stairs that seemed to creak more joyously under the winged tread. A tap at the door was followed by a vision of Elinor. Her bright face shadowed for a fleeting instant at glimpse of the tears. Myra glanced at her, and quickly the grieving corners of her mouth curved in delighted greeting.

“Something nice has happened,” she sighed expectantly, tucking her damp handkerchief into a ball and nestling her head farther into the hollow of Ruth’s arm. “Go on; I’m all right. Don’t you bother.”

“No, it hasn’t happened yet, but it will happen, I’m sure. Ruth, it’s a chance for you. One of the big magazines is offering a prize for the best story by a college student. You can do it. You can win it. Think of what that will mean! The announcement is published to-day. As soon as I saw it, I came a-running.”

Ten minutes later Myra’s heels clattered in swift staccato down the narrow stairs in her favorite rapid transit fashion. Dashing after Elinor she overtook her at the entrance to their study.

“You’ve made her happy, nice girl! Nice sweet dear girl! I want to hug you. She looked as if the sun had suddenly broken through the clouds. Funny person! Fickle, I call it, to forget Miss Ewers just because of an old magazine prize offer.”

“She doesn’t forget her, but there is no use in brooding; and this will occupy her thoughts. I know how it is to grow melancholy when I haven’t things to distract my mind and keep me busy, I am very glad I noticed the announcement.”

“So am I. So is Ruth.” In her joyous circling around her friend Myra managed to deposit a kiss on the tip of her ear. “You’re improving, too, same as Lydia. And Ruth looked at you — did you observe how she looked at you?”

“Why, no!” Elinor lifted her lashes in innocent questioning, but the iris seemed cloudy again as if withdrawn behind a veil.

“Well, she looked at you as if she liked you a lot — more than she likes me — ‘most as much as she always liked Miss Ewers. You’ve always been second, and now I guess you’re going to be first. I’m jealous.”

Elinor pressed her lips together.

“Yes, sir, I’m jealous. Here I liked you best from the very first glimpse I had of your curly head and charming smile and nice low ladylike voice. Though of course I didn’t see your voice exactly, but I heard it and I liked it and I like you, and Ruth needn’t think she is going to have more than a third of you or maybe half a third — “

“I do wish you would hush up!” fretted Elinor, “you’re getting sillier and sillier every day that you live. And she did push me away from her that first day — you know she did.”