Elinor’s Sophomore Year

CHAPTER IX

THE JEALOUS FATES

When the petition for permission to wear caps and gowns was rejected by the faculty on the ground that the desired costume was a relic of mediævalism besides being reprehensible as deepening the division between students and the outside world, Lidia bounced in her seat, shut her teeth, and listened in silence to the crestfallen comments. A few evenings later a meeting of the Students’ Association was summoned to hear a communication from the President of the College. It informed the student body that the faculty were not satisfied with the manner in which self-government laws were kept — or rather, broken. There was complaint of too frequent absence from the Sunday Bible lecture. A number of girls habitually disregarded their pledge to exercise an hour daily, and many appeared to translate ten o’clock as meaning any minute before the stroke of eleven.

The secretary had barely finished reading the note, before Miss Howard was on her feet; and acknowledgment from the chair loosened the floodgates of her verbal indignation.

Were they irresponsible children to be treated even with respect to clothes as if still in the kindergarten? Were they babies to be hounded on under espial to their duties? Was this a boarding-school with a faculty composed of petty detectives and a constituency of narrow-minded girls who delighted in evading a multiplicity of rules? Or were they a body of intelligent and educated women who had formed an association for self-government and were abundantly able to rule themselves without interference from extraneous authority?

Myra nestling beside Elinor far back in the crowded Chapel sighed with relief as the last sonorous polysyllable rolled forth over the motionless heads and Miss Howard resumed her place.

“Elinor,” she whispered, “aren’t we horribly bossed in this college? No wonder that you wanted to go abroad instead!” She was almost offended when Elinor, after a quick glance at her solemnly excited face choked suddenly and bent her head while the seat shook for several minutes.

Finally the motion was proposed and carried, in spite of Miss Howard’s strenuous protests, to select student officers for regulating neighborhood lawlessness. Everybody was urged to take her own seat in Chapel, and the girl at the head of each pew was instructed to keep a record of absences. As regarded exercise, the matter was left to their own good sense and also to their honor.

“And it is the only thing that is left to our honor,” fumed Lydia in the center of a group of malcontents in the corridor afterwards, “promise all you wish to, and then have the Association say, ‘The monitor will catch you if you don’t watch out!’ I intend to withdraw my name from the roll. I prefer to be openly and honestly under the surveillance of the faculty.”

“But — but, Miss Howard,” piped up a freshman voice, “you said that law is consistent with liberty. It was our first night at college. You said that the laws forbid crimes that no well-constituted individual wishes to commit, and that similarly our self-government rules prohibit certain acts which the sensible student chooses to avoid of her own good reasonableness. I wrote it down in my diary. Are things different now?”

Lydia certainly was never at a loss to clothe her thoughts impressively, padding out the slenderest to the proportions of the most rotund. After her concluding philippic, Myra wandered pensively away to the banisters where Ruth lounged with her shoulders propped against a pillar and her arms folded across her thin chest.

“I think I shall withdraw my name from the Association, too, Ruth,” she said, her eyes looking unusually big and serious. “It is dishonest to sanction an organization which pretends to false powers. That’s what Lydia said. If the system is to be called self-government, let it be self-governing, with self-imposed laws. You know, the faculty at the very beginning ordered the girls to put the three rules about exercise, sleep, and Chapel attendance in the constitution, and every student has to sign it. Really to be true to our principles we ought to refuse to obey laws thrust upon us by tyrants. The faculty should have no voice in our affairs; and then of course we can wear caps and gowns if we vote for them. Lydia is awfully reasonable.”

“Awfully,” assented Ruth, her whimsical dimple flickering at the corner of her mouth, “she can reason herself all around the block and back again and come out right every time. Fancy Lydia a rebel against authority! An influence in the community with a vengeance! Lydia, the born and bred conservative, law-abiding, punctual, the ideal citizen!”

“Ah!” sighed Myra with unconscious wisdom, “that was before the faculty rejected the petition — and she wanted it hard. Maybe if it had not been for running against that snag, she would never have found out that self-government is a farce.”

Now that Lydia, whether fortunately or not, had made the discovery, incident after incident, episode after episode, came trooping to range themselves upon her side in her defiance of a paternalistic government. The faculty threatened to cut short the Thanksgiving recess in future if the students failed to return promptly by Saturday night. The trustees denied an appeal for round dances at the annual reception.

The lady principal suggested that economy in flowers and simplicity in dress would be in better taste at the Sophomore Party. The steward sent in bills for contraband tacks on walls and closet doors at the rate of ten cents apiece. The student monitors protested against the practice of some earnest scholars who went to bed at ten and rose at half-past to study in order to keep the letter of the law relating to cuts. The official censor of the Monthly blue-marked Ruth’s first editorial.

After the Holidays, Lydia returned to College, emphatic in her praises of a university which she had visited. Chapel there was not compulsory, and the men could skip recitations unless on probation. They were not required to go to sleep at a specified time — (a nursery hour, indeed!). They got up when they pleased, and they exercised when they chose, and they kept dogs and birds in their rooms — if they wanted to, and they had liberty to go to the theater or anywhere without a chaperon. (At this point Myra told her frankly that she did not look very handsome when she drew down the corners of her mouth.)

Miss Howard declared that she was weary of being treated like an irresponsible idiot. What was self-government itself but a miserable compromise, as perhaps she had mentioned before? It would be fully as reasonable to inform a child that he was free to do as he liked, provided he did this, that, and the other thing.

“I don’t believe the faculty acts so for its own sake — or their own sake. Dear me! What number is faculty anyhow?” said Elinor.

“It’s an unlucky number for me,” grieved Myra, “with examinations almost upon us again. Ruth is the only one who has drawn a prize so far. I wish Miss Ewers were my particular friend, especially when she twinkles her black eyes at me in class. Dear Ruth, take me along the next evening you go to call. Tell her I improve most amazingly upon intimate acquaintance. It is better to dawn than to dazzle.”

The four girls were walking over a country road that winter afternoon. On either side lay snowy fields sparkling in the sunlight, each stalk of grass and brown weed springing from a tiny mound of white at its base. On the ridge beyond the billowy levels, rocks showed dark faces softly hooded with fluff amid evergreens that had shaken their branches partly free from the bending weight; for the snow had lain long enough to make good sleighing.

“She says that you are a refreshing young person,” said Ruth, stepping out of the trodden way at the sound of jingling bells behind them.

Gloom over the dubious adjective had barely begun to settle over the glowing face before it was dispelled by the flooding sunshine of a new idea.

“Girls, let’s catch on! It’s lots of fun to ride on the runners,” and she was off in pursuit of the farmer’s &led. The driver halted with a kindly invitation to jump in. Elinor gazed, a bit scandalized, till her tentative glance at Lydia revealed an astonishing light of approval.

“In the universities the men are supposed to do unconventional things continually. It is part of the beauty,” she was running now, “and — free — dom of — un — der — grad — u — ate — life.” And she clambered into the rough vehicle.

Tall Ruth followed, her sleeves and skirts flapping in the speed of her long stride so that she looked as if blowing to pieces. She arrived just as swift-footed Elinor went diving over the back into the straw at the bottom. “Doesn’t this seem good!” she sighed, “I am so tired!”

The driver chirruped to his horses, and away they all jingled, stray locks blowing about wind-tinted faces, eyes laughing, tongues calling — at least, Myra’s tongue was calling — “Oh, girls, isn’t it fun!”

They passed several groups of students who stood aside from the road while the gay party sped by. Some stared at glimpse of the familiar figures, and others waved their hands. At the lake, where a few score were skating in the cleared space at one end, Myra sent a whoop ringing across the ice. The answering smiles and envious nods shone after them as far as the Lodge gates. Springing to the ground, with enthusiastic thanks to the hospitable farmer, they hurried on down the snow-walled path to the dormitory. Ruth dimpled at an overheard colloquy: “Did you see those sophomores on that wood-sled?”

“Yes, but it’s all right, I’m quite sure. Miss Howard was one of them.”

By the next evening punging, as it was called, was undoubtedly the fashion. On every road roundabout, drivers of sleighs were besieged by crowds of laughing girls. Clinging forms swayed on the runners of swift cutters, and rows of snowy shoes hung over the sides of box-sleds. Forgotten hand-sleds were hauled out from the store-rooms beneath the buildings, and started on fresh careers of friskiness. The array of skaters upon the little lake was notably diminished.

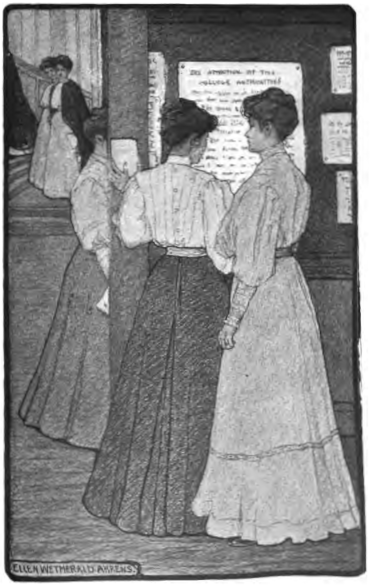

Three days of this sufficed to bring forth a placard upon the bulletin board :

“The attention of the college authorities has been called to the fact that some of our students have been asking strangers both within and without the college grounds to give them rides, or to allow them to fasten their sleds to wagons or sleighs.

“The students are reminded that requests of this kind, though made for the sake of a frolic, are quite as much out of order when there is sleighing as when there is none, and that in making them they are exposing themselves and the college to very unpleasant but not unjustifiable criticism.”

“I wonder what Lydia says to this,” commented Elinor, pausing on her way to the library when she found Myra, with her pad propped against a pillar, busily copying the notice for her memorabilia scrapbook. “I think it is just about right, tactful and dignified and true.”

“She said, ‘Boarding school!'” replied Myra with a comical little snort of imitation contempt, “she said it sort of languidly as if she were getting worn out trying to raise the standard all by herself. This kind of thing makes me weary too,” added the young lady, heaving a tumultuous sigh of utter exhaustion.

“But, Myra, now honestly don’t you think punging was a mistake? I haven’t dared to mention it in letters home. Fancy our begging rides anywhere else!”

“It’s the unconventional freedom of undergraduate life,” began Myra, ready as ever for a logical dispute, “it’s the principle of — “

“Girls, I am going punging this afternoon,” sounded Lydia’s voice distinct and vibrant behind them, “would you like to go with me?”

Two seniors standing near regarded her curiously. Her head in its becoming toque was held well back in a strikingly self-estimable pose, as Myra called it. Her chin was lifted at its most resolute angle. In the depths of her dark eyes smouldered the steady fires of unconquerable rebellion against oppression. Myra saw them.

“Crackie!” she muttered softly, torn between admiration and prudent memories of her freshman year, “what if you should meet Prexie?”

The determined chin went up a few inches higher. “Are we babies — “

“Oh, no, no!” Myra hastened to reassure her, “but we belong to this college and bear its name, and people certainly criticize it for what we do. Don’t you remember all those horrid newspaper jokes about chewing gum and sliding down the banisters? It’s a question of reputation.”

“Good-bye,” Lydia flung back over her shoulder, “sorry you won’t go.”

“I did my best,” said Myra virtuously and then stepped over to a window to send a longing gaze after the valiant figure stalking away down the snowy path. “Wouldn’t it be fun to go punging in such a splendid storm! Jingle-bells, jingle-bells — “

Elinor patted her elbow. “You were all right. It does make a difference whether a person is a member of an institution or is just herself alone. We have to show respect for the rights of ownership. Didn’t you read that novel where the heroine began to take better care of her lovely hair after she was married and realized that she belonged to somebody else, hair and everything. She was responsible to him.” Elinor paused for a reflective moment before adding with sudden energy, “I hate responsibility.”

“Same here.” Myra heaved a sigh. ” I never felt so when I was only a freshman, Nobody expected anything of us, but now — ” the blank was eloquent, “I suppose that the best we can do, being sophomores, is to put on our rubber boots and go to meet Lydia the next hour.”

The next hour saw the two girls, wearing gymnasium suits under their pretty cravenette coats, trudging along the snowy road. They seemed shut in alone together from all the world by a wall of soft white flakes falling ceaselessly. Myra ploughed through the drifts and turned up her face to watch the myriads of specks fluttering down endlessly from the boundless gray sky above. They melted in cool kisses on brow and cheek and chin. Elinor chose to walk in the wheel-ruts and hold her long coat just high enough to hinder the flakes from floating into the tops of her boots. She had not much reserve strength and tired quickly under such conditions. She grew silent and plodded on more and more slowly as the snow deepened underfoot. At last she cried for mercy.

“Myra, I can’t go a yard farther. How do you manage to be so brisk and lively at this time of year with the examinations coming next week?”

“I never hurt myself studying,” she answered with an extra joyous hop into the middle of a fluff-filled ditch, “neither did my mother; that’s one reason. Very well, we’ll start back, if you say so. I dare say Lady Lydia can take care of herself. Ah!” she cocked her head to listen, “quick, Elinor, jump out of the way. There’s a sleigh coming fast.”

Elinor sprang aside barely in time as from the blind chaos of snow-flakes around them a horse pushed into their tiny world, trotted with swift muffled hoofbeats across their field of vision, and vanished with the sleigh behind him into the vastness beyond.

“It was Lydia,” gasped Myra, “on the seat — with a baby in her arms.”

“The man looked like a farmer,” said Elinor, shaking the icy drops from her lashes, “they’re going toward the town. She’ll be late for dinner.”

Myra wondered all the way back to the college, but Elinor was too much exhausted to contribute conjectures. Her mind was divided between the hope of finding a dry place where she might sit down to rest and the vision of her mother’s disappointment if she should happen to fail in the impending examinations. When at last she dragged herself into the study and sank upon the couch, she was too tired to think of going to dinner. Consequently she was the sole occupant of the room when Lydia entered, flushed and bright-eyed, erect and energetic, with her most conspicuous air of executive ability rampant.

“What! Are you under the weather again? Elinor, I am certainly disappointed in the way you carry your work this year. There is no need for anybody to be sick if the proper care is taken. Are you sure that you could not conquer this weakness if you tried conscientiously? I am positive that in many cases it is a mere matter of will-power. Loot at me. Have you ever known me to fall ill?”

Elinor said nothing for a minute, except perhaps two or three words very low in confidence to the pillow at her side. Then she gathered her faculties together and half sat up. “I’m only tired from tramping through the snow with Myra. We saw you pass in a sleigh. Did you have any adventures while punging? Myra had her nose glued to the window for an hour before she went to dinner. There she comes now. They must have had rice-pudding for dessert, and she willingly sacrifices it to her anxiety for you.”

Myra dashed in. “I knew you had come. I felt the frost still eddying in the alleyway. Oh, Lydia, where was it? How was it? What was it? When was it? Who was the baby? Did you get kidnapped? Did you pung? Did you have a runaway? Did you get dinner in town? I’m simply crazy to hear all about everything. Did Prexie see you?”

“I don’t know, I assure you. Do you imagine that I watched the sidewalks, especially as they were invisible in the storm. I rode out into the country several miles in a wood-sled, and stopped at a farmhouse to warm my hands. The farmer’s wife and five children were feverish and had sore throats and other interesting symptoms. I advised him to buy a chest of homeopathic remedies and engage a nurse, as scarlet fever is all over town. He harnessed up, and I brought the baby in for his sister to keep till the others get well. I promised to send her a pamphlet on the care of children. Such ignorant persons do not know the first laws of health. If they would pay attention to proper air and food and exercise and bathing, their systems would never become devitalized enough to afford a foothold for germs.”

“But, Lydia,” objected Ruth, who had strolled in during this speech and noticed an exasperated twitch of Elinor’s fingers, “even the best informed people cannot always prevent disease. Consider all the worn-out doctors and dyspeptic professors. Some girls are not started out with robust constitutions in their babyhood. Others overstep the limits before they are aware. I used to think that I was made of iron and could work indefinitely until I found out otherwise. Even you ought not to take unnecessary risks.”

Lydia smiled condescendingly. “You thought you were made of iron; I am made of iron.”

“Oh, cr — r —” began Myra and suddenly broke off her expletive in the middle, from disgust at its feebleness before Lydia’s splendid self-confidence, “oh, you are,” she subsided weakly, “well, there’s the gong for Chapel. Let’s run along.”

Before following the two others she darted back to drop a kiss on Elinor’s ear and caught a petulant little cry, “Wouldn’t I be glad to see her knocked out just once!”

However, as fate decreed, it was Elinor herself who was knocked out by the strain of examinations, and spent a day or so in bed. At noon of the second day Lydia drew Ruth into the hall and threatened to send for the doctor.

“There’s nothing the matter except last week’s examinations,” remonstrated Ruth from the heights — or depths — of her own experience, “she’ll be around to-morrow.”

Lydia leaned against the wall in a limp posture markedly different from her customary brisk erectness. She brushed her hand across her brow with a weary motion that struck Ruth’s surprised attention.

“Girls are so foolish about allowing slight emergencies to upset their equilibrium. College should teach them poise, balance, common-sense. Three seniors are down with scarlet fever, and some freshmen have been sent home. Elinor ought to be more prudent.”

Myra in the doorway opened her eyes at the sound of a fretful note in the mellow tones. “I am never ill, and yet I take examinations and carry the ordinary amount of work and this extra bother over the Trig play is enough to make a wooden head whirl round and round.” She half raised her hand toward her forehead, but lowered it quickly at a restraining recollection of her principles. “It is a mere question of will-power. I don’t give up when I have an ache or a pain, for the sake of being petted and coddled and fed on steak and toast.”

“I don’t think you’re nice, one bit!” sputtered Myra, headlong to the defence, “just because you’re strong and well and everything, you haven’t any sympathy or understanding or anything. It would do you good to catch scarlet fever or something, and I just wish you would, so there!”

Lydia accepted this in such peculiar silence — not her ordinary regardlessness of inferior planets, but rather dazed and dumb, as if she barely comprehended the hurrying words — that Myra veered even more swiftly than usual to contrition. “I wish you weren’t so provoking,” she grumbled, “but Elinor doesn’t collapse for fun — not by a j — jug —— not by a carafe-ful!”

“You certainly are improving,” laughed Ruth; but Lydia did not seem to notice.

The afternoon stretched out endless and dark before her. Wearily she plodded from one recitation to another. She did not skip even the hour in the gymnasium, though the task of putting on her suit and tying the sailor’s knot at her throat loomed up in anticipation as a tremendous exertion. During dinner when the others commented on her lack of appetite, she felt a burning of the eyes, and rose hastily to withdraw before the senseless blush could spread higher into sight. While plodding slowly up to her room, she heard steps following, and summoned all her forces to move with characteristic buoyancy. Each foot dragged as if weighted with a pound of lead. How heavy her head was! Was it really bending first to one side, then to the other? The corridor reached on and on, the rubber matting apparently rising in gray waves that tumbled like the ocean. She feared that she might stumble over the next billow, for her feet grew heavier and heavier.

Then somebody’s arm slid around her; and she leaned back, conscious only of the blessedness of being supported. Ruth’s fragile strength failed under the burden ; and Lydia sank gradually to the floor. Sitting there in a relaxed heap she looked up mistily at the anxious face bending above her.

“I can’t get up,” she moaned; “I don’t even want to try. Oh, what is the matter with me?”

When Myra heard that Lydia had been taken to the scarlet fever ward in the infirmary, even while her eyes were yet rounded in awed sympathy, she rushed away to beg a can of tar from the janitor. Upon being set to simmer in her best fudge-pan, it caught fire promptly and was flung blazing out of the window, while a black column of smoke rolled through the transom into the corridor.

“What would Lydia say?” asked Elinor, leaning out to see where the tar was casting up a final flicker from its dark spot on the snow.

“She would say,” began Myra, and interrupted herself to put her head out of the door in response to a hail of knocks. “No, it isn’t a fire. It’s tar — a disinfectant — reasonable precautions, and so forth. Ruth, dear, kind, sweet Ruth, please write a sign about that tar and pin it outside, will you? I’m getting hoarse already. She would say that it isn’t any of the faculty’s business anyhow; but I know I shall be called up to explain to-morrow. The ceiling does look rather sooty.”

“Poor Lydia!” murmured Elinor, and paused, smitten by the idea that this was a novel epithet for superior Miss Howard; “it means six weeks in the infirmary.”

“And losing all the fun of Trig Ceremonies and Valentine’s Day and Washington’s Birthday and the Third Hall Play and Easter and concerts and — “

“And her work,” put in Ruth, soberly, thankful that she as well had not been taken captive by some mischievous-minded germ.

“She’ll know how it feels now,” said Elinor ; and then glanced up guiltily from under her lashes to see if the others had noticed the unexpected little ring of exultation in her voice.